We get asked this question quite a lot! As Permaculture becomes more and more popular and perhaps projected as a wonderful solution for diversity and abundance, it is a general perception that “being a Permaculture farm” is the next big innovation in farming.

We get asked this question quite a lot! As Permaculture becomes more and more popular and perhaps projected as a wonderful solution for diversity and abundance, it is a general perception that “being a Permaculture farm” is the next big innovation in farming.

My first answer is ‘NO!’, and my second, in classic permaculture style, is ‘it depends.’ We employ Permaculture design principles where needed and possible, but that does not define the farm.

I have had the privilege of studying and working with some exceptional Permaculture teachers and practitioners from India and across the world. I took the Permaculture Design Certificate course in 2014 and the Permaculture Teacher Training Course in 2016. So this explanation comes from an informed place, a place of deep gratitude for Permaculture but also a place of recognition of its limitations.

Permaculture was conceptualised by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren in the 1970s in Australia, in response to the crises of industrialised agriculture that intensified with the Green Revolution of the 1960s. They drew on the Aboriginal worldview, a philosophy of life that has sustained people for millennia without degrading the land, and on systems thinking, a then-emerging approach that studies the whole rather than just the parts. Combining these perspectives, they proposed a regenerative landscape design through which humans could practise sustainable, permanent agriculture, giving it the name “Permaculture.”

Essentially, Permaculture is a design system. Design has long been a vital tool for human beings, enabling us to imagine and create. We are all designers in some way, using it moment to moment — thinking, planning, visualising, and adjusting with feedback. Over time, design as a discipline became more elaborate, shaping professions that relied on visualisation, spatial planning, architecture, product development, technology, and the power of imagination. Yet in the last couple of centuries, the means and tools of design have evolved so rapidly that the almost godly power it confers can sometimes turn the designer against the designed, and even against life itself.

What makes Permaculture unique is that its design process is founded on three key ethics:

Care for Earth Care for People Fair Share

By placing these at the core, Permaculture calls on the designer to weigh every decision by its impact on the land, its people, and all forms of life. Echoes of these ethics run through ancient traditions and modern ecological thought, and Permaculture weaves them into a coherent, practical framework for action.

The principles of Permaculture are the guidelines for turning its three ethics into practice. They can be applied to systems of any scale, in ecology, communities, or even in one’s personal life. While many practitioners adapt or reinterpret the principles to suit their context, they all rest on natural patterns of circularity, interconnectedness, diversity, flexibility, and cooperation. From these principles emerge strategies such as earthworks, water and soil conservation, and community-based work. Bill Mollison outlined many of these in Permaculture One and Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual in the 1980s, and since then they have been applied and expanded upon by practitioners around the world.

Permaculture is a rapidly growing movement in India, attracting people dissatisfied with the status quo and seeking to reconnect with nature, learn integrated design, or grow their own food. Permaculture offers a strong foundation for working on the land, cultivating a sense of design, and developing an integrated approach to planning — skills especially valuable for those moving from cities to smaller towns and villages in search of a simpler, more meaningful life. Across the country, the number of groups and professionals offering design consultations and courses keeps growing and the community continues to share their challenges, successes, and conclusions here. However, many courses are urban-centric, catering to newcomers without deep farming experience; imported temperate-climate techniques sometimes need significant adaptation for tropical conditions; and short-term enthusiasm can fade if not grounded in daily practice and community support.

Today, Permaculture extends far beyond agriculture. Within a few decades of its inception, the founders recognised that a permanent agriculture solution alone was not enough; creating such systems also required rethinking how people live and work together. This gave rise to social permaculture — an expansion from permanent agriculture to permanent culture. Over the years, it has captured the imagination of many, especially urban dwellers seeking a new language to imagine different possibilities. Yet such growth also brings dilution: Permaculture has come to mean many things, from crop diversity and organic farming to food forests and local food, and sometimes, as a result, it risks meaning nothing at all. It is certainly all of these, but not only these, and it resists absolutes, always seeking to understand the context and build from there. In my observation this enthusiasm for Permaculture can also sometimes overshadow the purpose of the work and a deeper, long-term relationship with land and community.

There is a concept in Permaculture called invisible structures, the subtle relationships that hold physical reality together. On a farm, for example, visible structures include the soil, water, plants, and infrastructure; the invisible ones are the relationships among the people working the land, their ties to the wider community, and the economic exchanges that sustain them. While the visible is rooted in the physical landscape, the invisible is grounded in the landscape of the mind.

Permaculture recognises the need to design and cultivate this inner landscape as much as the outer, yet it avoids explicit conversation about spirit or consciousness. This was intentional: the founders wished to keep it from becoming another new-age “thing,” positioning it instead as a science people could test and adapt anywhere (Wright, 2021). But this has left a mind–spirit split. In India, for example, some have tried to integrate Yoga and Permaculture, yet often without sufficient depth in one or both. And if such integration were successful, would it still be both, or would it have become something entirely new?

For any new agricultural practice, I believe it is vital not only to acknowledge the spirit but to actively cultivate a language of consciousness, of the land, the community, and the farmer. As valuable as it is, Permaculture does not yet offer this.

Let’s nuance that question:

No. The farm is fifty-seven years old and its major layout is already established. We make incremental changes each year in response to Auroville’s evolving realities and the community’s needs. From a permaculture perspective, we are still in the “observation phase”. In permaculture, this phase means slowing down, noticing patterns, and allowing the land’s character to guide interventions, something we continue to practise because the farm is dynamic and never “finished.”

Yes — though our ethics are rooted in Integral Yoga, with its emphasis on deep relationality, evolution, and service. The ethics of Permaculture fall naturally within this scope.

Absolutely. We design by observing natural patterns, using resources mindfully, obtaining yields, learning from feedback, integrating land and people, valuing diversity and the marginal, favouring small and incremental solutions, and creatively responding to change. Are we successful all the time? No.

Yes, but we don’t use all the strategies, and not all our strategies come from Permaculture.

In the end, AuroOrchard is simply a farm. We don’t subscribe to any particular “-ism.” Permaculture is one of the tools we use, not the goal itself. Farming here is not about applying a fixed template, but about an ongoing conversation with the land, guided by multiple streams of knowledge and a shared commitment to growth, both of the soil and of ourselves.

We are also part of an informal network of permaculture and agroecology practitioners across India. While we don’t run a formal Permaculture Design Course (yet!), we host interns and researchers, exchange knowledge with other farms, and sometimes integrate ideas from these networks into our work.

“We have a legend that explains the formation of the hills, the rivers, and all the shapes of the land. Every time it rains and I see a beautiful rainbow I am reminded of the legend of the Rainbow Serpent…

In the beginning, the earth was flat, a vast grey plain. As the Rainbow Serpent wound his way across the land, the movements of his body heaped up the mountains and dug through for the rivers. With each thrust of his huge multicolored body, a new landform was created.

At last, tired with the effort of shaping the earth, he crawled into a waterhole. The cool water washed over his vast body, cooling and soothing him… Each time the animals visited the waterhole, they were careful not to disturb the Rainbow Serpent, for although they could not see him they knew he was there. Then one day, after a huge rainstorm, they saw him. His huge colored body was arching from the waterhole, over the treetops, up through the clouds, across the plain to another waterhole.

To this day the Aboriginals are careful not to disturb the Rainbow Serpent, as they see him, going across the sky from one waterhole to another.”(From “Gulpilil’s Stories of the Dreamtime”, compiled by Hugh Rule and Stuart Goodman, published by William Collins, Sydney, 1979.)

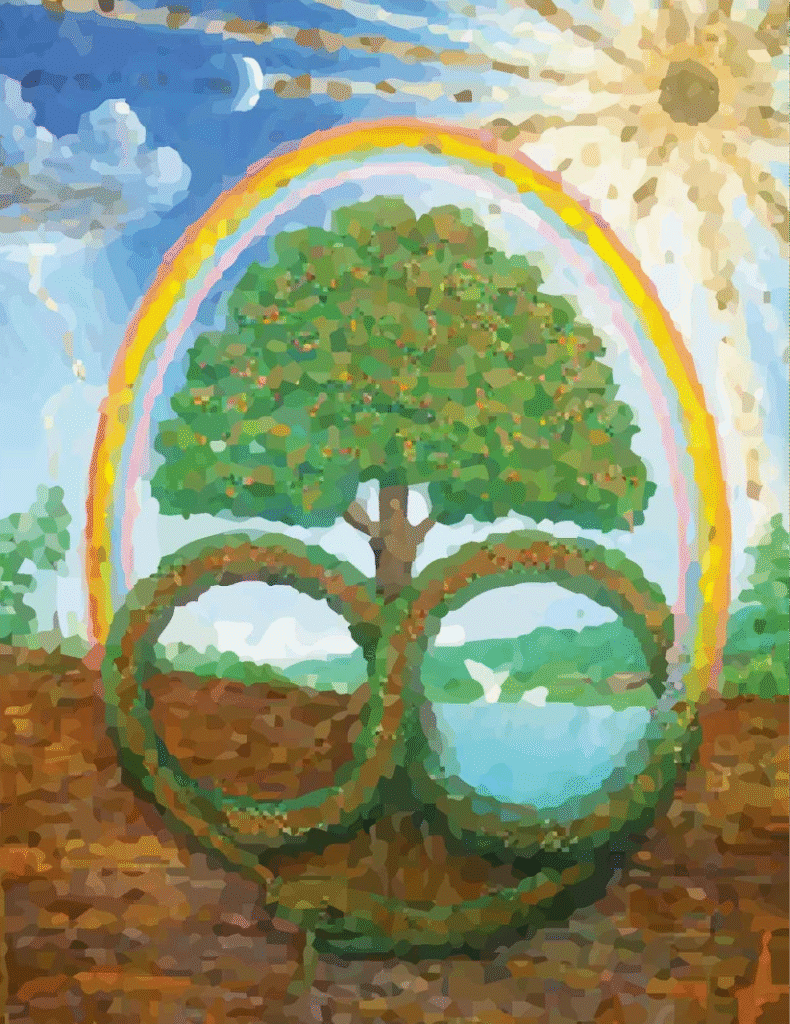

Permaculture symbol: The rainbow serpent coiled around the eternal egg of life and containing the tree of life, surrounded by the elements of the earth, rain, wind and the sun, representing the interconnectedness and complexity of life on this planet.

McGowan, Meg. 2019. “Systems Thinking in Permaculture.” Smarter Than Crows (blog), April 12, 2019. https://smarterthancrows.wordpress.com/2019/04/12/systems-thinking-in-permaculture/ SMARTER THAN CROWS

A Short and Incomplete History of Permaculture. Pacific-edge, July 2007. https://pacific-edge.info/2007/07/a-short-and-incomplete-history-of-permaculture/ Food Tanksites.middlebury.edu

Nierenberg, Danielle. 2015. “Sixteen Successful Projects Highlighting Permaculture Use.” Food Tank, July 6, 2015. https://foodtank.com/news/2015/07/sixteen-successful-projects-highlighting-permaculture-use/ Food Tankagrodite.com

Permaculture Ethics Explained. Deep Green Permaculture, June 22, 2016. https://deepgreenpermaculture.com/permaculture/permaculture-ethics/ Deep Green Permaculture+1

Fair Share: The Controversial 3rd Ethic of Permaculture. Worldwide Permaculture. https://worldwidepermaculture.com/controversial-third-ethic-permaculture/

Social Permaculture – What Is It? Institute for Cultural Enterprise (blog), 2016. https://www.ic.org/social-permaculture-what-is-it/ Foundation for Intentional Community+2resilience+2

Permaculture Methodologies. Food Security and Nutrition Network (PDF workbook). https://www.fsnnetwork.org/sites/default/files/Permaculture_Methodologies_WB.pdf fsnnetwork.org

Chapter 3: Permaculture Design Strategies and Techniques.” Permaculture Guidebook (online chapter). https://permacultureguidebook.org/product/chapter-3-permaculture-design-strategies-techniques/ permatilglobal.org

The Difference Between Organic Gardening and Permaculture. Permaculture Visions (blog). https://www.permaculturevisions.com/difference-between-organic-gardening-and-permaculture/ permaculturevisions.com+1

Site Design Strategies – Permaculture. Heathcote (website). https://www.heathcote.org/PCIntro/6StrategiesTechniques.htm Ibiblio

Werner Heisenberg: Explorer of the Limits of Human Imagination. Fritjof Capra (blog), 2016. https://www.fritjofcapra.net/werner-heisenberg-explorer-of-the-limits-of-human-imagination/ oac.cdlib.org+3fritjofcapra.net+3accademiapeloritana.it+3

Wright, Julia. “Re-Enchanting Agriculture: Farming with the Hidden Half of Nature.” In Subtle Agroecologies, pp. 3-20. CRC Press, 2021.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351822051_Re-Enchanting_Agriculture

Join our newsletter for exclusive updates!

AuroOrchard is certified organic by the Tamil Nadu Organic Certification (ORG/SC/1906/001683) Department accredited by APEDA (Agricultural and Processed Food Products Exports Development Authority), New Delhi, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India.